Dean Worcester's Fantasy Islands: Photography, Film & the Colonial Philippines by Mark Rice (review)

- Aug 19, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Jun 27, 2024

by JPaul S. Manzanilla |

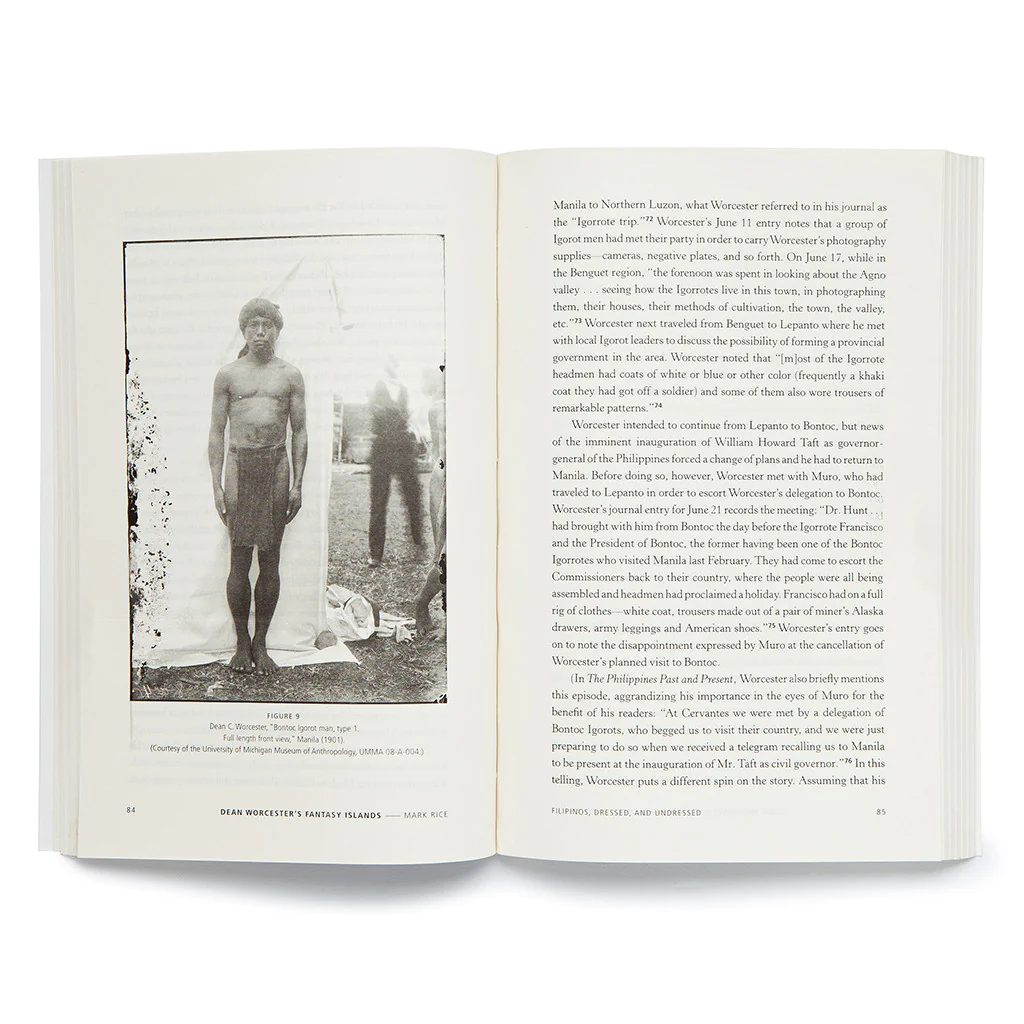

Fig. 1. Cover of Dean Worcester’s Fantasy Islands: Photography, Film, and the Colonial Philippines by Mark Rice. Image from Artbooks.Ph: https://artbooks.ph/products/dean-worcesters-fantasy-islands-photography-film-and-the-colonial-philippines

Mark Rice

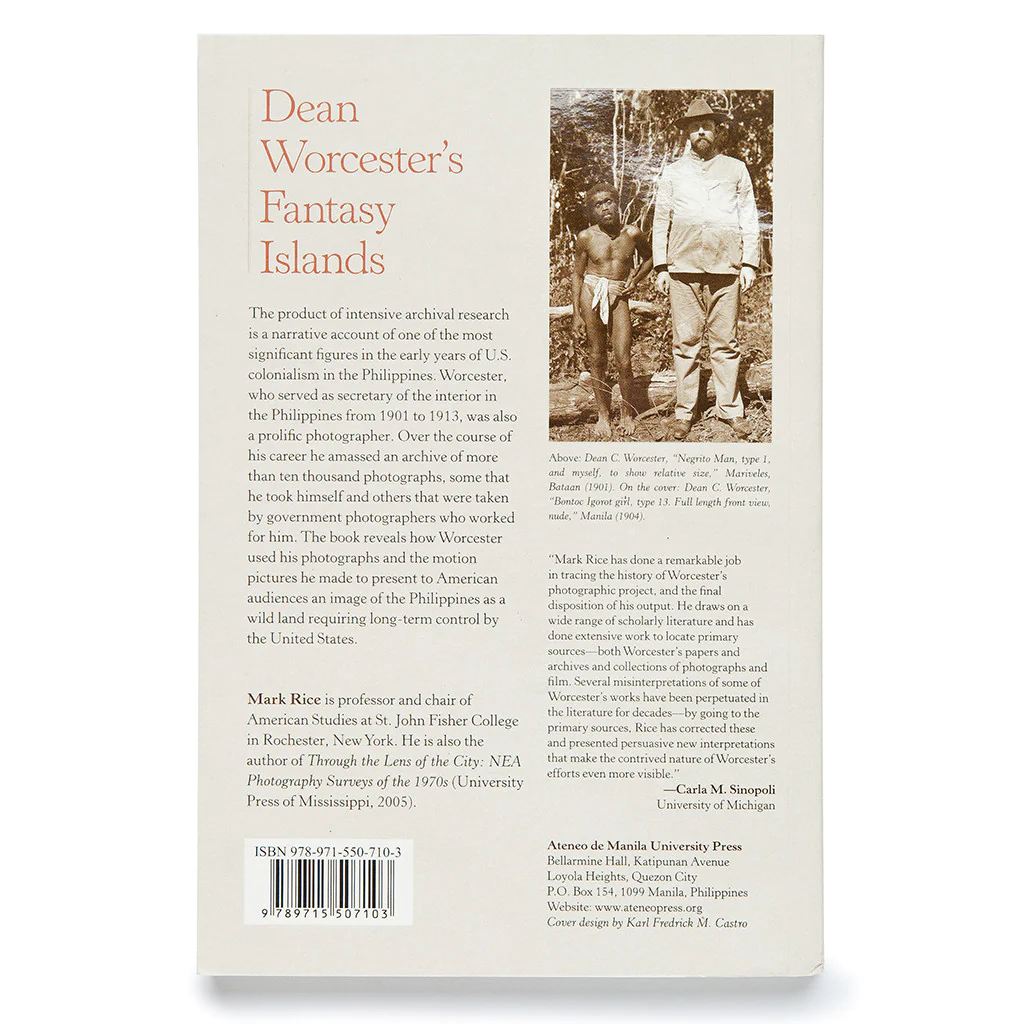

Dean Worcester’s Fantasy Islands: Photography, Film, and the Colonial Philippines

Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2015. 270 pages.

Before Dean Worcester’s Fantasy Islands was published, the only book-length study of American colonial photographs of the Philippines was Benito Vergara Jr.’s Displaying Filipinos: Photography and Colonialism in Early 20th-Century Philippines (University of the Philippines Press, 1995). Vergara showed how the country was “visually possessed” by means of travel pictures and made to represent the colonial narrative of progress through the use of before-and-after images in official photography of the state. While Displaying Filipinos tackled official and travel photography of the early years of American rule, Dean Worcester’s Fantasy Islands focuses on a huge photographic collection of one of the most important personalities of US imperial rule: that of zoologist, ethnologist, public official, and entrepreneur Dean Conant Worcester.

Worcester was an exceptional person of his time. He had visited the Philippines while it was still a Spanish territory, collecting specimens as part of a scientific expedition. When the question of the country’s future was being debated and later on when it became a laboratory of colonial rule, he shared his knowledge with American officials, a knowledge he later fashioned as “expertise.” Much of this expertise was derived from his prolific production—and strategic use—of photographs. Readers should note at the outset that not all photographs were taken by Worcester himself; the man, in fact, asserted authenticity of pictures from the “scientific and governmental credentials” of the photographers (42).

“Establishing the Archive,” the first chapter, leads us to the primary sources of the author’s study. These voluminous documents are not innocent products of Worcester’s documentary zeal; they are object lessons for understanding some of the prevailing technological, scientific, artistic, and political imperatives of the period. It is telling that Worcester did not submit to the camera’s presumably truthful nature; he believed that it “can be made to tell the truth” (2), reminding us of the agency that lies outside the medium and debunking an idealist conception of truth as something that only has to be told. He communicated the truth of and about his subjects—the Philippines and its people—through skillful utilization of the camera, its attendant photographic processes, and the subsequent ways and means of displaying the “objective” pictures to various peoples. His use of photographic technologies, developments of which he was so attentive to and which he maximized, buttressed the special knowledge of the Philippines that Worcester claimed. On this point, it is important to consider the epistemological implications of the ontological condition of photography, which here does not simply mean the physical snapshot but also the procedures of its production and most importantly the materiality of its exhibition, display, and circulation—indeed, its constitution as a “photography complex,” according to historian James Hevia.

The second chapter tackles what may be considered the most observable feature of Worcester’s photographic subjects: the Filipinos’ states of nakedness and nudity. Rice uses the descriptions “dressed” and “undressed” to highlight the “symbolic uses of clothing as markers of savagery and civilization” (48). Naked and partially covered bodies are dense images that reveal the photographer’s dispositions to capture them and the eventual reader’s prejudices in how to see them. We all know that they were not seen for “what they were,” but according to certain assumptions of how human beings should appear and what “proper” citizens of a modern nation and state should look like. Because being photographed is being controlled, photographed bodies were posed according to the visual predilections of the photographer. The erotics of capture and display, the pedagogical mission to appraise Filipino natives as being closer to African Americans and even label some of them as the “missing link” to man’s primate ancestor (52), and the close scrutiny of the human bodies and their parts to the point of scientific “exactitude” are practices that demonstrate that knowing the people of America’s first colony entails subjugating others in the process of enlightening Americans at home. And Rice exposes a lie. The famous and frequently reproduced Igorot sequence presenting a three-picture set of a man “gradually advancing” from being a partially clothed and slouching “wild” man to an upright and formally clothed member of the Philippine Constabulary was only fabricated to convince fellow Americans and the world of the beneficial effects of colonialism. The pictures were not taken in successive years: the clothing in the second photograph was not related to the Constabulary; and the three men were not the same person! Only the first two men are the same person, in fact; he was Don Francisco Muro, a noble man of the Bontoc ethnolinguistic group who was able to negotiate with the Americans (80).

Fig. 2-4. Inside pages of Dean Worcester’s Fantasy Islands: Photography, Film, and the Colonial Philippines by Mark Rice. Image from Artbooks.Ph: https://artbooks.ph/products/dean-worcesters-fantasy-islands-photography-film-and-the-colonial-philippines

Chapter 3 deals with Worcester’s representation of the Philippines to a wider audience through the mass-circulated and very popular National Geographic Magazine. Rice argues that “Worcester was anything but a marginal figure in that magazine’s emergence as a major publication in the early twentieth century. Indeed, Worcester’s photographs were at the very center of the entwined histories of National Geographic and American colonialism” (95). Abundant with pictures, his articles published from 1911 to 1913 became pivotal in representing the islands to the world. They enabled images of a previous terra incognita, i.e., the Philippines, to enter the homes of millions, rendering the colony a visual personal possession. His visual taste was the determining factor for graphically illustrating the country. Rice details how Worcester performed this process by highlighting the diversity and “savagery” of its peoples and their “progress” during American rule, publishing bare-breasted women that lured more viewers (hence, the perception of the magazine as almost pornographic), and sharing 1903 census photographs that enabled scrutiny of morphological features and facilitated comparison among peoples, races, and nations. The reproductive power of photography hence popularized the twin ideals of “commercial expansion” and “moral tutelage” (112). Worcester’s depictions verged on the messianic, submitting a view that non-Christian Filipinos, to be saved, depended on him and American tutelage.

Rice’s penultimate chapter discusses how Worcester brought his ethnographic documentary campaign to a special audience that would affect perceptions of and decisions on US governance of the country. The indefatigable Worcester delivered dozens of lectures at civic gatherings in different parts of the US to shape public opinion in favor of continuing colonization. He contrasted the different stages of development of ethnic groups and therefore stressed their heterogeneity and the absence of a Filipino people or nation, and cleverly utilized still images to depict “savage” peoples and motion picture to emphasize developing subjects of empire. He earned huge sums of money in the process. In the last chapter, the author pursues how Worcester’s photographic projects effected “very real consequences” with “distinct political value” (184) when he served as a resource speaker at hearings conducted by the US Senate Committee on the Philippines, finally resulting in the passage of the Jones Act or Philippine Autonomy Act of 1916, which did not have any provision on the definite time of Philippine independence. We learn then that Philippine sovereignty—or its deferment or negation—was anchored on a distinct visual production of the nation. The hermeneutic circle of Worcester’s photographic project was now coming to a full close. From his participation in ethnological work in the last decades of the nineteenth century to his role as an expert detailing the conditions of the islands, Worcester went on to serve as the country’s first Secretary of the Interior (1901–1913), politically governing the peoples he studied and (mis)represented. He ended his career as a successful businessman exploiting the riches of their territories.

All throughout his work, Rice belies claims of photographic transparency, objectivity, truthfulness, naturalness, and “unmediatedness” when he points out how Worcester: slyly employed captions to profess representativeness of persons as types and impart particular truths about their social and cultural maturity; used the same photos for different objectives; muddled identities, times, and dates; applied focus, distance, color, cropping, and framing to mean differently; and juxtaposed images to evoke “contrasts” among various groups of peoples within the country and between Filipinos and Americans. The book comes at a time when the archives of US imperial rule are inexhaustibly being read to understand how the colonial endeavor was implemented and ferociously defended through the ways native subjects were represented.

A number of recent works in Philippine studies carried out critiques of ideology by using the tropes of “dreaming” and “fantasy” as an approach to understand the symbolic production of the racial, class, and gender Other. Yet a major weakness of the book is the absence of an explanation for the conceptual underpinnings of the author’s term “fantasy islands.” Was the archipelago a projection of colonial desires of an other place and time, unbelievably utopian and thus too “unreal” that it had to be produced through the realist medium of photographs? Or was the tropical colony too (negatively) different that it had to be politically—and photographically—conquered, governed, and assimilated, thereby rendering its otherness a vanishing one, but memorialized in pictures? The necessity of contrivance directs us to the material form and practice of photography, on the one hand, and the subliminal operations of fantasy, on the other, but the author has to carefully connect the two.

Scholars, particularly of history and anthropology, American and empire studies, history of photography and visual culture, and Philippine studies, will benefit from reading this book. Tracing the movement of photographs from the field to government documents, newspapers, magazines, social halls, and on to the archives, Dean Worcester’s Fantasy Islands shows us how the picturing of native subjects is a tenacious effort to know, and enforce power upon, a seemingly irredeemable, because intractable, colonized.

2017

JPaul S. Manzanilla

Department of Southeast Asian Studies, National University of Singapore

<jpaulmanzanilla@u.nus.edu>

This text was first published in Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints. This article is republished with permission from the Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints and the Author.

Manzanilla, JPaul S. Review of Dean Worcester's Fantasy Islands: Photography, Film, and the Colonial Philippines, by Mark Rice. Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, vol. 65 no. 4, 2017, p. 546-550. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/phs.2017.0042.

Comments