Shifting Parameters

- Anna Rafanan

- Jun 24, 2024

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 20

by Anna Rafanan

Fig. 1. Augustine Paredes,“Into A Void”, 2022. (Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com).

when talking about a migrant heart they know nothing about it they only know of the grandeur glamour gold that all the stains can be wiped off with kleenex and it goes away but it is rust not stain rust from the dagger struck into the middle of the migrant heart and the sparkle is not sparkle but glimmer from the blood soaked floor (accompanying text for “A Migrant Heart”, Augustine Paredes, 2022)

What does it entail, as an artist, being/becoming diasporic? Often this constitutes an origin and a destination, creating a sense of place while grappling with an all-consuming embodied awareness of moving forward with uncertainty. What persuades the migrant artist to seek and yearn for belonging elsewhere?

The conditions that had paved the way for massive labor migration from the Philippines saw its beginnings during the Marcos Regime (1960s-1970s) as a result of the simultaneous occurrences of globalization, the laborer’s pessimistic outlook towards their homeland, and government institutionalization of labor codes that further solidify and normalize this continuous exodus. In effect, this exportation of labor becomes both an enticing enterprise for foreign countries seeking to minimize labor costs and a promising prospect for Filipinos wanting to alight and improve their social class status.

As a result, this labor trade has become the lifeblood that drives the Philippine economy. In the social domain, Filipino migrant workers bring with them their subjectivities and partake in a cultural exchange as an adaptive mechanism to the host country they choose to reside in.

The Filipino migrant worker experience has been the subject of contemporary media and scholarship. Deeply coded within Philippine culture are portrayals of the struggles of migrant workers. It has become embedded in the consciousness of every Filipino and to some, migration has become a pathway to reimagine their futures, to once and for all build a fitting home. For the migrant worker, making sense of their place in a world now bound by a globalized labor market becomes essential in grounding their sense of meaning and purpose. For this paper, I turn to art and art practice to depict a nuanced portrait of the Filipino migrant worker artist particularly in the Arab Gulf region. This essay offers a reading of selected works from Augustine Paredes’ oeuvre to bring to the surface, or as the artist suggests, to quarry the narratives that underpin a migrant artist’s practice. His body of work regards photography as a medium in the conception of the Philippine, intimately interrogated through art practice, operating between nation and diaspora. Being situated between here and there connotes an informed set of subjectivities and identities that intertwine and provide the context for his works. His practice is an epitome of Lavie and Swedenberg’s contesting of “old certainties”, that an “immutable link between cultures, peoples, or identities and specific places” does not neatly apply when aspects such as migration come into play (1996). In analyzing Paredes’ poetics, what arises is a counter-narrative, a unique lens in looking at the way participating and ascribing to a diasporic art practice challenges preconceived notions of culture and identity, nationhood and belonging.

Displacement

Fig. 2-4. Augustine Paredes, “Cooking Adobo At the Hea(r)t of 25.2048° N, 55.2708° E” Series, 2019.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Augustine Paredes is a Filipino artist currently based between Dubai and Frankfurt. He began his career as a photographer in the Philippines. In an interview with Daniel H. Rey, Paredes narrates what prompted him to leave for Dubai:

I was offered a photographer’s job in 2016 and left the Philippines out of a whim. I just said goodbye to my mom, and “here we go, Dubai.” And it was also because of a heartbreak. I was heartbroken when I left the Philippines and kind of ran away from that place where it broke my heart. (Rey, 2020)

In his photo series “Cooking Adobo in the Hea(r)t of 25.2048° N, 55.2708° E” (2019), he captures the adaptation that migration demands. He refurnishes the portrait of a home with ingredients sourced from a grocery in Dubai: an opened plastic bag of potatoes, sliced onions, smashed garlic, spoonfuls of soy sauce and vinegar, and one whole chicken. This adobo that alludes to the Philippines and his keen sense of home is spread across a dark background. The adobo that he cooks with these ingredients recreates and conjures a nostalgic representation of his homeland. Coupled with the first photo is a handwritten note, a recipe for surviving a rite of passage that a migrant worker knows all too well. This series of photographs are self-portraits of a migrant worker wanting to belong while adapting to his current home. Paredes hints at a softening: an opening up to a foreign land while at the same time carrying with him his subjectivities.

Fig. 5. Augustine Paredes, “Am I Driving Safely, If Not Please Call”, 2021. (Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Fig. 6. Exhibition view, Augustine Paredes, “Am I Driving Safely, If Not Please Call” Series, 2021.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

At the on-set, his body of work draws his audience into an intimate portrayal of his sensibilities through the abstraction of his photographic subjects. As in poetry, he draws from and puts forth fragmented vignettes in his relentless pursuit of belonging. In a year-long mentorship program with Warehouse 421 and Gulf Photo Plus, he was commissioned to capture and portray the changing landscape of Mina Zayed, the first local port in Abu Dhabi that contributed drastically to the economic and political status of the UAE within and around the region. In “Am I Driving Safely, If Not Please Call” (2021), Paredes’ lens focuses on the minute details of the place. Details of the bustling port are printed on loose-flowing banners hung in succession. Photo prints hung on the walls engulf the reader which forces them to make sense of the landscape while evoking a playful inquiry into its setting.

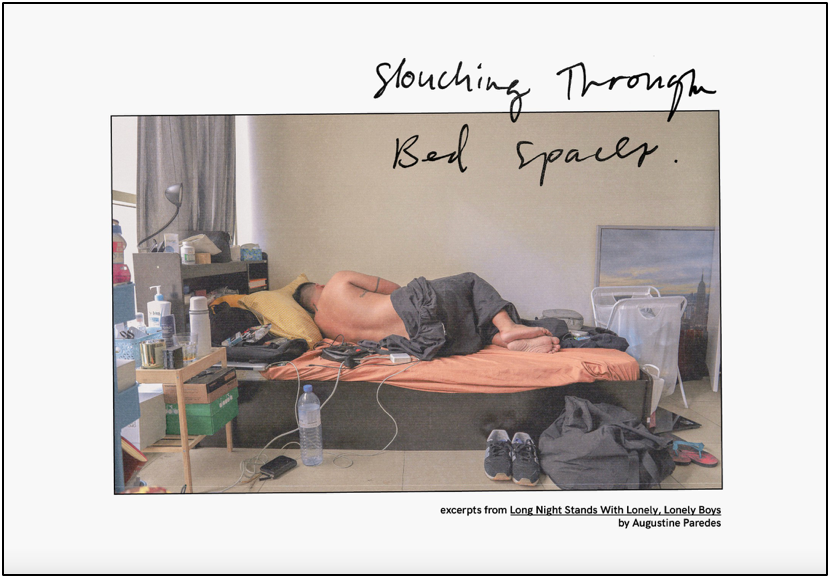

Exposition

This quest to explicate meaning challenges the artist to become multi-faceted. Having gained confidence in embodying his art practice, Paredes began to engage in mediums beyond photography to produce his works. For a commissioned work in a group exhibition at Warehouse 421, “Good Night, Sweet Dreams” (2021) portrays the malleability of a photographic image. His self-portrait, lying in bed, back towards the viewer, is printed on a cloth draped over a bed frame. This is an iteration of a photo in his series “Slouching Through Bedspaces” (2021) that he self-published in his book “Long Night Stands With Lonely, Lonely Boys” (2021). His half-naked figure succinctly fits as the bed’s skin in the exhibition space. He draws parallelisms between the small spaces he inhabits and escapes from through his migration: his bed space in Dubai and his embodied queer identity. He masterfully hides and hints it to those who are willing to read his poetics, a consequence of living in a predominantly conservative Muslim country.

Fig. 7 - 9. Exhibition view, Augustine Paredes, “Good Night, Sweet Dreams”, 2021.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Filomeno V. Aguilar Jr. details the ways that labor migration has changed the socio-historical, cultural, political, and economic domains of the Philippines. He treats the migrant subject as one who undergoes a ritual passage, a pilgrimage. He writes:

“In undergoing the travails of overseas work, the labor migrant’s subjectivity is aligned and transformed in ways only partially glimpsed at the start of the journey; but in the course of the sojourn abroad the migrant becomes reflexively aware of the reconstitution of selfhood as anxieties and uncertainties are replaced by a new subjectivity.” (2014)

In 2020, Augustine Paredes co-founded the Sa Tahanan Collective alongside Anna Bernice Delos Reyes in Dubai. They mounted their first exhibition as a fundraising event for the victims of Typhoon Goni back in the Philippines. He began to pursue painting under the persona of Clementine Paradies, whose works he mounted for the collective’s first exhibition. His use of mirrors in “Welcome Home” (2021) and “Absence of Commas and Apostrophes” (2021) provides portals for reflexivity.

Fig. 10 - 11. Left: “Welcome Home”, 2021; right: “Absence of Commas and Apostrophes”, 2021.

(Images courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Fig. 12. Excerpts, Augustine Paredes, “Long Night Stands With Lonely, Lonely Boys”, 2021.

(Image courtesy of the artist and Goethe Institut)

Fig. 13. Excerpts, Augustine Paredes, “Long Night Stands With Lonely, Lonely Boys”, 2021.

(Image courtesy of the artist and Goethe Institut)

Early interest in poetry prompted him to compile an epistolary assemblage of his photographs with his acquired vocabulary of loss, grief, and love in his book, “Long Night Stands With Lonely, Lonely Boys” (2021). It started as a photography project in 2014 and it maps his interiority of what it means to migrate and explore his yearning for affection. With his handwritten words, letters, notes and poetry contributions from friends and lovers, he chronicles his pursuits in Dubai, Davao, Stockholm, Yerevan, Beirut, Tbilisi, Paris, Berlin, and Helsinki.

Augustine Paredes subverts the act of censorship that is strictly imposed on queer bodies here. His use of abstraction through collages of photographic works with handwritten poetry dismantles the body and defaces portraits of lovers. Passion and affection seep through his meticulous fragmentation of portraits. He bares the body naked without obscenity, he uses a visual language that is soft without vulgarity. Paredes’ exploration of a passionate migrant heart culminates in his first solo exhibition in the UAE aptly titled “Paradise 4Ever” (2022).

Paradise

Being diasporic informs Augustine Paredes’ art practice. Exile, perhaps, might even heal a diasporic heart. What lies beneath the surface is inevitably quarried. In his “Paradise 4Ever” exhibition, he alludes to innocence in his childhood through the tale of the velveteen rabbit that becomes real when given the right amount of affection. His sense of self leaps from artwork to artwork as he shapeshifts into the poetics he evokes through his works.

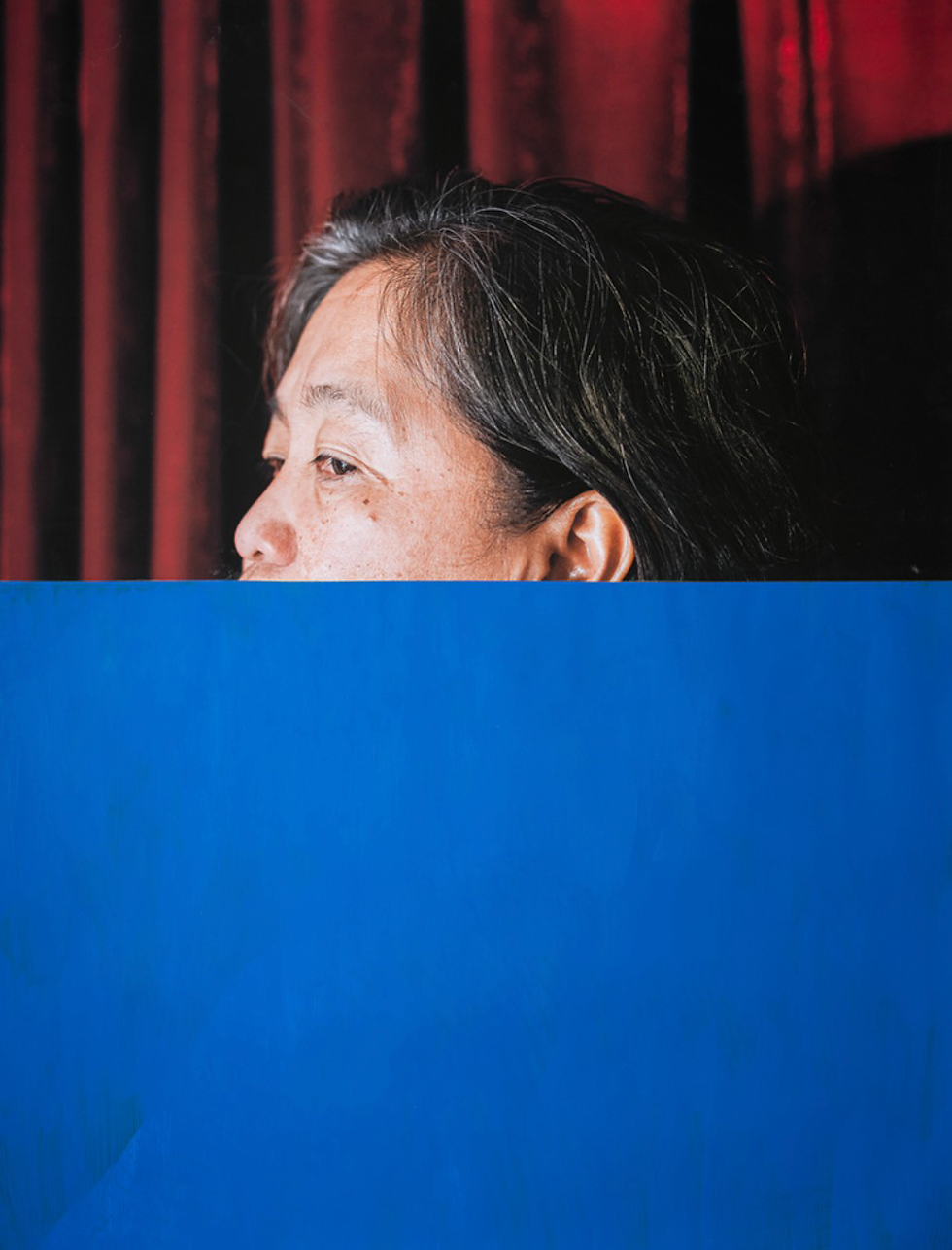

Fig. 14. Accompanying poetry for “Into A Void”.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

In “Into A Void” (2022), he wears a rabbit mask at the back of his head as he poses away from the camera. He sits in front of an imagined horizon of foliage theatrically framed with velvet curtains. He presents an immaculate image of the migrant in “Healing a Migrant Body” (2022): the body seems upright but, on close inspection, is still lying down and covered in white linen. He forces the migrant body to resurrect, over and over—a self-portrait that opposes all of his works in the room. His face though resting is very much visible but averts the viewer's gaze, a photograph he did not deface or burn. It can be gleaned from his works an electric blue that calls to mind the ocean in a constant state of ebb and flow. He painted his skin in the same hue in “Portrait of a Poet Dancing I to V” (2023) where Paredes fluidly moves in a dance he captured in five frames. At the heart of his exhibition is a portrait of his mother, half-bathed in this suffocating emotive hue. He mirrors a child’s departure from the caring arms of his mother, a parallel to how a migrant worker leaves their motherland, recalling the face of their mother that they glance at before leaving.

Fig. 15. Augustine Paredes,“Healing the Migrant Body”, 2022.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Fig. 16. Augustine Paredes,“Mother”, 2022.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Fig. 17. Installation view, Augustine Paredes,“Portrait of a Poet Dancing I to V”, 2022.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Narratives that Paredes portrays stem from hope and nostalgia. He presents a nonprescriptive map of what it entails to reach and keep reaching paradise, something to strive for and to arrive at. The works he has exhibited in his first solo exhibition abroad at Gulf Photo Plus, Dubai, UAE are syncretic in nature and put into consideration existing milieus that operate on tense, seemingly opposing binaries.

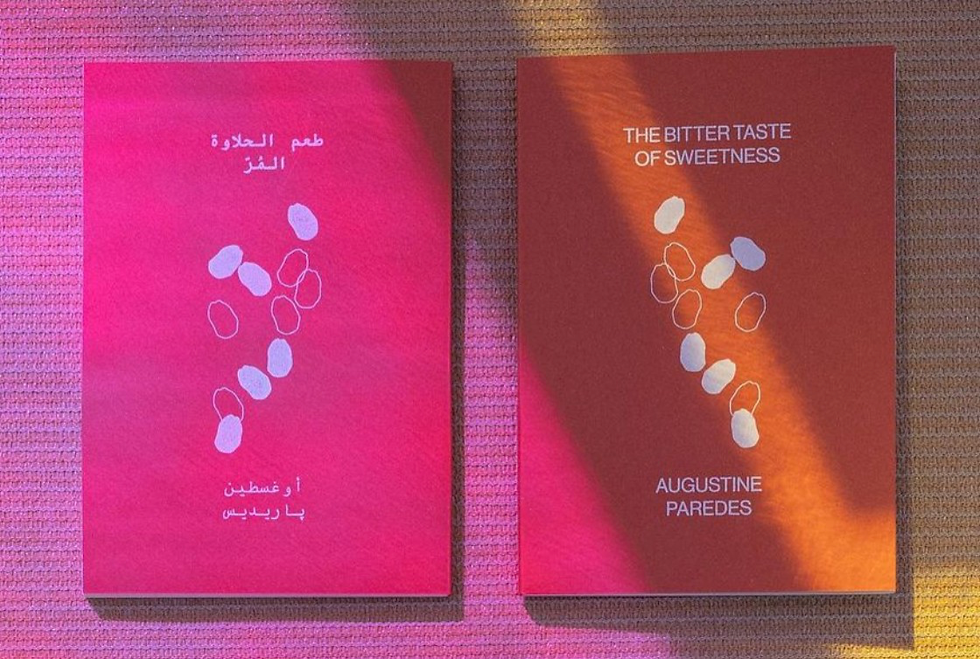

Augustine Parades’ participation in residencies and mentorships further solidifies his art practice within the Gulf Region. He is an alumna of the AlUla Artist Residency, Salama Bint Hamdan Emerging Artist Fellowship, and Campus Art Dubai. His site-specific installation for his AlUla Artist residency in Saudi Arabia, “The Bitter Taste of Sweetness” juxtaposes the date farmer with his memories of farming back in the Philippines. The iridescent facade of the pavilion shimmers amongst the date palms that surround it. The pavilion houses his paintings that are products of his observations of the farming cycle of dates, at once a disruptive culling of the fruit and a rewarding pursuit of harvest.

Fig. 18. Installation view, Augustine Paredes,“The Bitter Taste of Sweetness”, 2023.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Fig. 19. Accompanying text and poetry for “The Bitter Taste of Sweetness”, written in English and translated in Arabic.

(Image courtesy of the artist; augustineparedes.com)

Recognizing that the diasporic intent further gives nuance to the ties that inevitably bind an artist’s practice with the homeland is a necessary act in meaning-making. The artist’s embodied subjectivities can be likened to a “moving constellation that mutates every time it comes in contact with other constellations” (Patrick D. Flores in Palumar, 2019). Augustine Paredes challenges the notion that identity is inevitably tied to a place of origin. Rather, he conceives an identity more intimately linked to his sense of place. His art practice shapeshifts to accommodate the multiple contexts that he embodies. As Stuart Hall writes: “[t]here is always the inevitable slippage in the open semiosis of culture, as that which seems fixed continues to be dialogically re-appropriated” (2001). His status as an artist allows him to negotiate his subjectivities within the locale that he inhabits and materializes. His is a practice that provides a discursive interruption of the migrant worker persona, no longer a mere laborer but also a participant in the advancement of a Philippine art history elsewhere.

2023

Comments