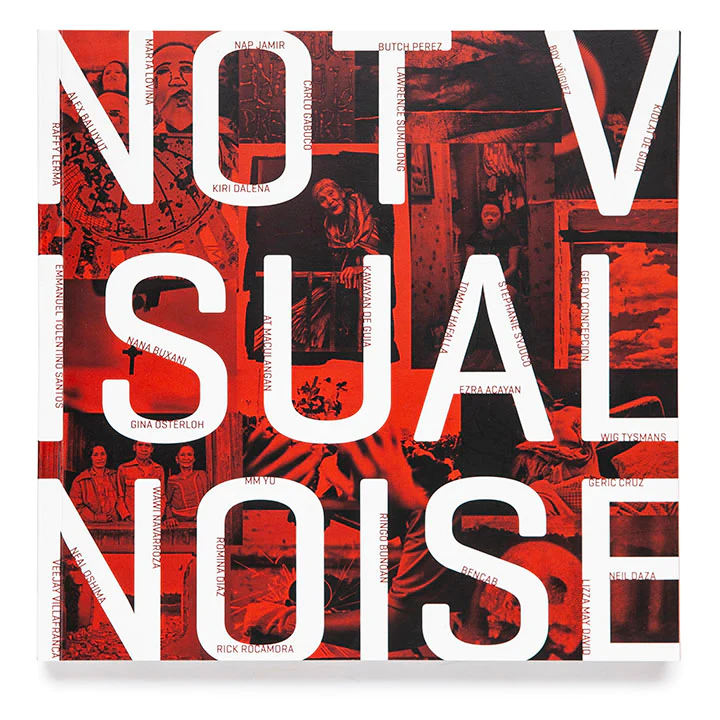

NOT VISUAL NOISE: Philippine Photography In A Media Saturated World

- Aug 19, 2023

- 15 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2024

by Angel Shaw | 2019

Fig. 1. NOT VISUAL NOISE, curated by Angel Shaw. Image from Ateneo Art Gallery: https://ateneoartgallery.com/exhibitions/not-visual-noise

There’s so much visual noise that it’s hard to make work that is distinctive and focuses the attention of the crowd in a sustained way.1 ~ Susan Meiselas

The photograph has meant and continues to mean a plethora of things to the population of the world since 1839 when the photographic image was assured mass ubiquitous reproduction. The approximately 1.62 billion daily Facebook and 500 million Instagram daily users’ barrage of photographic images remind us of the mundane, yet, profound value of photography as a form of human expression—immortalized recordings of personal and collective cultural, social, and political events and life experiences.

The reasons for taking photographs of specific content and contextualization utilizing a combination of technologies vary from image maker to image maker. It is in the eyes of the beholders to determine if such imagery contributes to visual noise or not, is a form of artistic practice, or spans the categorical compartmentalization and outward appearances of homogeneity. The internet, social media, and new media technologies guaranteed that our world would be inundated with visual noise. Such noise is the norm.

Nowadays, the actuality that “everyone” can be a photographer goes without saying. The categorization of photographers as amateur, citizen, professional, commercial, documentary, photojournalist, art, hybrid––whether their photographs are seen in social media posts, on the street, retail stores, galleries, museums, or homes––is self-imposed and/or sanctioned by the culture industries in which they work. Despite the blurring boundaries of the hobbyist, professional photographer and artist, the categories are contradictory and inescapable.

Curator, critic, and founding director of the Documentary Photography and Photojournalism Program at the School of International Center of Photography, Fred Ritchin succinctly states, “The incredible malleable photograph––whether manipulated before or after the shutter’s release––is employed to fashion the world according to the intentions of the person making it, or the institution for which it is being made. The world and we become one...refracted together in a self-portrait, basking in the glow of Image while disingenuously unaware of how frayed the connections have become between the photograph and the world it was once meant to signify. We are insulated...”in our own image.”2 In theory, if photojournalists, documentary photographers, and artists who use photography work with deliberation, they are not adding to the noise. One person’s sense of “visual noise” may not be the same as another’s. Similarly, photography is thought to be a medium that captures, records, and is a witness to “truth”. Yet, one person’s truth may not be the same as someone else’s truth. Photography as a non-static visual language is heterogeneous and evolutionary in its functionality, meanings, and messages.

The Not Visual Noise exhibition concept was inspired by reading Zhuang Wubin’s comprehensive chapter on the history of Philippine photography roughly spanning 1895–2012 in his seminal book, Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey, the enthusiastic reception of the Provocations: Philippine Documentary Photography exhibition I co-curated with Neal Oshima for Art Fair Philippines 2018, and my own personal history with traditional documentary and contemporary photography as a visual and media artist.

Fig. 2. Invitation and exhibit map for NOT VISUAL NOISE. Image from

Ateneo Art Gallery: https://ateneoartgallery.com/exhibitions/not-visual-noise

I invited twenty-three Philippine-based and eight artists in the Filipino diaspora to think about key phrases and words when deciding about the kind of photographs and photography-based artwork they would like to contribute to the exhibition, whether original or older theme-specific works. The inclusion of Geloy Concepcion, Lizza Mae David, Romina Diaz, Gina Osterloh, Rick Rocamora, Emmanuel Tolentino Santos, Lawrence Sumulong, and Stephanie Syjuco who reside in the U.S., Germany, Italy and Australia, was paramount in introducing Philippine-based viewers to Filipino diasporic artists’ works seldom seen in the Philippines. Their back-and-forth movement to their real and imagined homeland, and creative practices are, to some extent, informed by these experiences.

Key Phrases:

Þ Visual noise

Þ Not visual noise

Þ Citizen or amateur photography

Key Words: Þ Verb: To document

Þ Noun: Document

The exhibition’s central questions were: What is the role of a photojournalist, documentary photographer, conceptual and multimedia artist using photography in today’s media-saturated world? How do these creatives choose to represent the social, cultural, and contemporary art issues that concern them? What does it mean to expand the documentary category beyond traditional and stereotypical boundaries?

The primary goals of this ambitious undertaking were to showcase the scope of Philippine photography from the latter part of the 20th century to present day and create greater exposure for documentary photography and its range of reinventions in contemporary art practices not normally exhibited together in any cultural venue, let alone mainstream cultural institutions.3 As a whole, the photographers and artists distinct works represent the nuances within and across the fields of Photography—from photojournalism, long-form documentary photography to conceptual, photography-based media installation, and web/social media-based projects.

Art exhibitions dedicated to photography as an art form in the Philippines began as early as 1967 when Ben Cabrera (now a National Artist) and his older brother, Salvador, featured the works of five photojournalist/documentary photographers in their short-lived Indigo Gallery. In subsequent decades, art galleries, cultural institutions, restaurant-bars, and artist-run spaces based in Manila like Silverlens, Calle Wright, MO_Space, the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Penguin Café, the Right Spot, Oar House, Lumiere, Third Space, Big Sky Mind and Surrounded By Water, and Café by the Ruins and V.O.C.A.S. in Baguio City continued in this trajectory.4 Yet, some gallerists, museum directors, collectors, artists, photographers, students, teachers, and the general public continue to question the validity of photography as an art practice. This is due to a general lack of awareness, interest in, and exposure or access to national and international art and photography histories in formal and informal settings. Unfortunately, educational and financial support for Philippine culture, heritage, and the arts remains in an imbalanced push/pull dichotomy.

Fig. 3, 4. Installation views from NOT VISUAL NOISE. Image from

Ateneo Art Gallery: https://ateneoartgallery.com/exhibitions/not-visual-noise

British essayist and novelist, John Berger aptly stated in his 1967 essay, Understanding a Photograph, “By their nature, photographs have little or no property value because they have no rarity value.”5 Paintings and sculptures continue to be upheld as high investments. However, as of this writing, the gamut of photography is gaining traction as being collectible in greater numbers, at least in Manila.6

Conversations with the artists about their exhibition concepts and seeing their works-in-progress confirmed that their seemingly divergent perspectives are convergent. They are in fact, documentarians of their interests, aesthetic, and social concerns, and of the times in which they live, albeit not all in the strict definition of the word.

Emerging, mid-career, and established contemporary conceptual photography- based artists like Ringo Bunoan, Lizza Mae David, Nap Jamir, Marta Lovina, Wawi Navarroza, Gina Osterloh, and Stephanie Syjuco are exhibited side by side with photojournalists like Raffy Lerma and Ezra Acayan, documentary photographers / photojournalists such as Alex Baluyut, Nana Buxani, Rick Rocamora, and Veejay Villafranca. All of these participants are, in one way or another, creating and constructing documents in traditional or hybrid forms of documentary practices. Their photographs and installations exemplify the multidimensional range of photography-based approaches, and perspectives exploring specific cultural and socio-political issues in critical reflexive ways today—whether as creatives practicing in the Philippines or in the diaspora.

A confrontation with the ongoing argument about whether or not photography is a form of art across and within the spectrum of high and low culture, and high and low art, is inherent in the calculated positioning of the artworks in the Ateneo Art Gallery’s four galleries. The museum’s brain-shaped floor plan lent itself naturally to arranging the works organized in clustered themes which loosely corresponded with the brain segregated by lobes. The photographers and artists concepts, content and photographic approaches were juxtaposed within, between, and across each gallery in ways that enabled viewers to contemplate these pieces individually and as they moved in and out of each space. The curatorial plan and group exhibition consciously challenged notions of passive spectatorship, compassion fatigue, the credibility of photographic images to represent reality, beauty, collectability, past and current theories of photography, conceptual art, and the intersection of theory and practice.

Filipino photojournalists and long-form documentary photographers have been documenting daily life, human conditions, and social conflicts as early as the 1930s, overlapping with corresponding western modern and post- modern/contemporary art movements. Many of the photographers and artists represented in the Not Visual Noise exhibition had their beginnings in these traditional forms of photography and later parted ways with them, creating in hybrid media platforms and/or utilizing whichever medium suits their ideas best while still using the photographic image as its base.

Ezra Acayan’s Duterte’s Fake War, dramatic photographs printed on wood and Raffy Lerma’s Inhuman, “war”-on-drugs series, poignantly depict the current government-sanctioned genocide in an unflinching manner. San Francisco- based Rick Rocamora’s Intifada Marawi and Freedom and Fear: Bay Area Muslim-Americans after 9/11 provide intimate close-ups of the severe damage caused to Marawi’s mosques, other city structures, and dwellings after the siege, and candid daily life of Bay Area Muslim-Americans after 9/11, respectively. The collocation of the two events speaks to the global plight of everyday Muslims who are casualties of the fanatical religious conflicts that surround them. Life Masks, Kiri Dalena’s thespian-like portrait series of political activists and artists began in 2013. In 2018, she shifted her concentration to the families affected by the extrajudicial killings, using her more metaphoric experimental cinema and aesthetic sensibilities to create empathy for their largely ignored predicaments. These four artists’ haunting images invite the viewer into their subject narratives’ fraught spaces, despite perhaps one’s unease to turn away.

Fig. 5. Installation views from NOT VISUAL NOISE. Image from

Ateneo Art Gallery: https://ateneoartgallery.com/exhibitions/not-visual-noise

Seasoned photographer Alex Baluyut chronicles his life in his photographic/video installation, Recipes for Disaster––sharing his two great passions, documentary photography and cooking, as it relates to his humanitarian work as founding president of the Artists Relief Mobile Kitchen NGO. One can see how his quest for truth and social justice morphed into helping displaced victims of natural and manmade catastrophes archipelago wide. In Australia-based Emmanuel Tolentino Santos’ artist statement, he describes his thirteen-year project, “Witness”: Tikun-Kadosh (Sacred Healing)) installation as a homage to succeeding Polish generations of Jewish people who perished in the Holocaust as he poetically addresses how history is alive.

Geloy Concepcion’s memoir of his young family’s immigrant life in the San Francisco Bay Area, SANCTUARIO Unang Yugto: Ang pakikipagsapalaran ni Isagani sa bansang Amerika comprises 100-plus images. Veejay Villafranca’s multimedia lenticular prints and zine, Barrio Sagrado: Living with Religiosity and Catholicism in the Philippines, were inspired by his investigative journalist grandfather exploring the complexity of Filipino religions; contemporary photographer Wawi Navarozza’s darkroom installation and photographic/video assemblage, By Silver, By Light (Ang larawan maoy tuburan sa mga paghandum sanglit maoy mo pukaw sa dakung kalimot) is a homage to the photography of Cristituto Navarroza, Sr.; and Berlin-based media installation artist Lizza May David’s The Mangrove Selection, was initially inspired by specific family members and their life experiences. Wawi and Lizza utilize appropriation—all furthering their inquiries into cultural representation and insider/outsider dynamics, each paying tribute to specific family members while addressing issues of migration, commemoration, archiving, authorship, and worship in their works.

Three generations of Baguio based artists and photographers––National Artist Ben Cabrera (BenCab), Tommy Hafalla, and Kidlat de Guia––each knowledgeable about American Imperialists’ misrepresentations of indigenous peoples and cultures, employ a wide variety of photographic techniques to render agency to those that were stripped of their dignity. Tommy has been documenting the landscapes, daily life, customs and rituals of the people in Kalinga, Mountain Province, Benguet, and Ifugao provinces in the Cordillera region since 1978.

BenCab’s digitally manipulated portraits of young Ifugao farmers posing in their daily field clothes superimposed wearing their Sunday bests dismantle stereotypes of the indigenous as primitive with singular identities. His colorful signature swooshes of paint blend with the photographic image, merging all of his passions—painting, printmaking and photography in a unique way. Documentary filmmaker and photographer Kidlat’s Manong series weaves stripes of two color photographs creating portraits that reference the significance of weaving in the Cordillera. These diverse and reverential pieces are reflective of the Cordillera peoples who have adopted them as one of their own.

Composition, texture, light, and depth-of-field are a few shared traits between photographers; cinematographers; and documentary, feature narrative, and experimental filmmakers. The serial documentary photographs of Nana Buxani, Neil Daza, Butch Perez, Boy Yñiguez, and the multimedia installation works of Nap Jamir and At Maculangan allude to their dexterity in these image-making mediums. In cinematographer Neil Daza’s humorous piece Whoever Said That One Shooting Day Is 24 Hours?, he depicts the undeniable long hours of the film and television industries in one-hundred images of sleeping actors, extras, and crew members. The intimate portraits of Hazel Adrao, a factory metalworker, are part of Nana Buxani’s larger ongoing series about workers throughout the archipelago. The nucleus-like arrangement of images in Hazel Adrao, Welder/Assembler pays tribute to her subject’s multiple identities as worker, wife, daughter, and breadwinner.

Feature film director Butch Perez, who began his illustrious career as a conceptual photographer in the 1970s, tells two intertwining evocative stories about the unseen and visible effects of WWII on the artist and his family and Baguio City, a former American hill station in his artful black and white prints Ruins and Relics. These sparse cinematic depictions of ruins in1980, accompanied by two photographs of narrative prose reveal personal and historical loss. Cinematographer Boy Yñiguez’s Berlin U-Bahn 1 Subway series of sixty-six (66) analog prints of subway passengers on a main subway line simulates his experience of also being on the train. Moving from each handwritten, time- stamped 22.86 cm x 15.24 cm image to the next, one feels as if she/or he is sitting across from these German commuters through his masterful photographic framing.

Fig. 6, 7. Installation views from NOT VISUAL NOISE. Image from

Ateneo Art Gallery: https://ateneoartgallery.com/exhibitions/not-visual-noise

Conceptual artist and cinematographer Nap Jamir continues his photographic explorations, delving into the malleability and effects of tearing fiber-based photography paper, and the digital manipulation of an image in three distinct serial pieces called Underbelly. Collages of torn photographs consisting of fragmented ambiguous body parts, twigs, leaves, and soil are transformed into textural (Fragments) and sculptural (Reflections) deconstructed and ultimately, reconstructed ruminations. Nap’s elaborate multimedia installation, also titled Underbelly, comprises three wood-framed jalousies that frame nature photocollages which, in turn, frame 30-minute, video environments. These deconstructed, imagistic “windows” and actual elements from nature––leaves, soil, twigs––echo as well as add to the experimental provocativeness of the other cluster of artworks and vice-versa.

For the Not Visual Noise exhibition, conceptual artist and experimental filmmaker At Maculangan resurrects his character, Juan Gapang, in his multimedia installation Today I Am Not Feeling Well, from his 1986 short experimental film which he co-directed and performed in. On an old television, a young At can be seen crawling around Metro Manila, “searching for his destiny”—symbolic of the plight of the everyday Filipino during the height of the EDSA Revolution. In his macabre and yet, comically staged photographs and photographic standees, the aged Juan Gapang/At is now seen at present, the time of another dictatorial regime. One could argue, that these two artists’ works exemplify what art historian and cultural critic TJ Demos refers to as “the reinvention of documentary photography”7, despite the fact that neither of them would consider themselves to be documentary photographers. Yet, they incorporate documentary strategies.

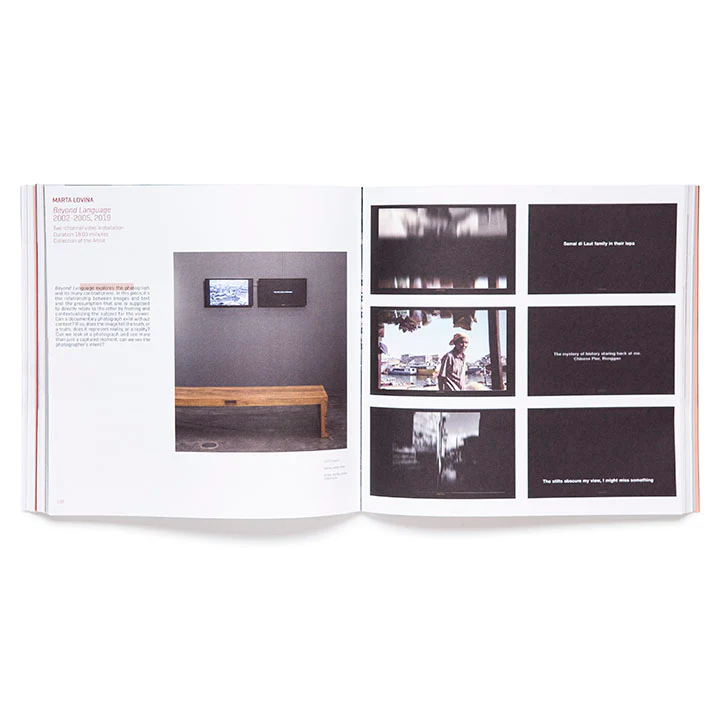

The concept of “randomness in documentary photography” can be perceived as an oxymoron. While it is possible to take a “random” photograph, the intent behind taking a photograph of an object, event, portrait, landscape, or community environment does exist. There is a thought process––whether conscious, unconscious, or somewhere in between. Of course, happy accidents can inevitably occur even if one frames a shot or waits for the ideal opportunity to shoot. The serial documentary photographs of Geric Cruz (Pakiramdan Explosion), a matrix of mundane images, were arranged on the wall in a calculated manner and Marta Lovina’s Beyond Language, a two-channel video installation on a Sama Dilaut nomadic sea-faring community in the Sulu archipelago, is ironic and paradoxical. The photographs, presented like a slideshow on one monitor and scrolling texts consisting of ethnographic field notes and journalistic captions at varying speeds on the other, read like flipping through a visual library card catalog. Some images and texts are in sync and make sense. At other times, they are throwing the expected relative meaning out of sync while still creating meaning. Cruz’s and Lovina’s creative processes are embedded in their treatment of seemingly arbitrary 35mm camera and digital iPhone photographs. There is, in fact, order to these familiar images of urban and provincial life.

San Francisco-based multidisciplinary artist Stephanie Syjuco’s conceptual 1:25:52 minutes video, Index Digitalia rides the fine line between being visual noise and being the artist’s intellectually playful response to it. Five thousand and one hundred eighteen (5,118) one-second jpegs of personal notes, receipts and bills; snapshots of people and places; personal and student art works and exhibitions; print, photographic and web-based advertisements; architectural and natural landscapes; Filipino postcards and historical images of the Spanish and American colonial periods; textbook pages, etc. appear to be arbitrary, but are actually systematic. These alphabetical computer- generated images were exported directly from her personal laptop computer’s database. Syjuco’s fascination with archives, archiving, ecosystems, and technology industries is ever-present.

Contemporary photographer MM Yu (Subject/Object) resists categorization as a traditional long-form documentary photographer. Like many of her peers showcased in the Not Visual Noise exhibition, she traverses definitions of what it means to document, problematizing the binary slash between “subject” and “object”, subjective and objective. Both Yu and veteran photographer Wig Tysmans (Himself, Herself, Themselves) create serial portraits of artists, some of whom are also participants in the exhibition. The former focuses on one-hundred and one (101) nameless Filipino artists’ studios and their objects, while the latter features nude portraits of artists and actors based on how they imagine themselves, over a thirty year period of time. Their works, as well as those of Gina Osterloh, Emmanuel Tolentino Santos, Kiri Dalena, Tommy Hafalla, BenCab, Wawi Navarroza and Kidlat de Guia in the Alice P. Lorzeno Gallery illustrate the multifarious approaches to portrait photography in traditional and contemporary photography contexts.

Fig. 8, 9. Catalogue for Not Visual Noise. Image from Artbooks.Ph: https://artbooks.ph/products/not-visual-noise

Conceptual artists Ringo Bunoan and Gina Osterloh are part of the lineage of postmodern artists whose concepts are the works of art while simultaneously representing more than one social issue as seen in their critical reflections on monuments and women as Othered objects of desire. Ringo’s Untitled Monument is a critique of photography’s problematic ability to record historical events, how and what is recorded and is not. She fabricated and photographed a scaled- down façade of an unrealized WWII Heroes monument on Corregidor Island. Whether or not she was actually able to preserve a significant era in Philippine history in a photograph is precisely what she calls into question. Gina’s multi- component piece, Pressing Against Looking, juxtaposes performative self-portraits and steel-plates with the welded wordplays “Pressure/Pleasure and Pleasure/Pressure”, to explore the politics of looking as it relates to body and identity politics, amongst other issues referencing photography’s visual language. In keeping with Nap Jamir’s conceptual photography practices, both women, call upon their viewers to pause and contemplate setup photography as a means to convey their complex concepts.

Photography, as the omnipresent recorder and preserver of the ecosystem of memory, is the dominant motif running throughout the exhibition. Neal Oshima mines his early graduate works, Pulped (1977) on hand-made paper pulp and continues his investigation on abaca fiber paper, (Mnemonic Triptych, 2019) with inlaid fragments of maps, charts, travel, and vintage photographs focusing on the dubious nature of memory, climate change, and colonialism. Romina Diaz’s This Puzzling Progress entices the audience to reconstruct a 9,000-piece puzzle, image-memory of a demolished apartment building destined to give way to a new condominium or mall. Using the stereoscopic Viewmaster toy, Filipino- American photographer Lawrence Sumulong (Dead to Rights) lures the user into three self-contained narratives depicting the human conditions in Manila. These photographs, shot over a period of eleven years, captured moments in time that feel timeless. Carlo Gabuco’s innovative multiplatform piece, The Other Side of Town, is composed of noir-like color digital portraits and documentary images with accompanying zines with QR codes that link to the same portraits’ unsentimental audio stories on Vimeo about being Martial Law torture victims and Marcos cult members, told in candid, heartfelt ways. Utilizing multiple media technologies provides Filipino audiences with new opportunities to see and hear photography-based accounts of people and events that resonant today.

Fig. 10. Catalogue for Not Visual Noise. Image from Artbooks.Ph: https://artbooks.ph/products/not-visual-noise

The illusive nature of photography as a means to capture truths, conjure memories, and document history is exemplified in De:Compositions, Kawayan de Guia’s oversize photo album. The tactile and otherworldly qualities of his one hundred photographs of friends, family, indigenous people from the Cordillera, landscapes, and objects with tracing paper overlays of expository writing reify the impermanence of memory and the photographic image’s ability to contain it. Nature or, more specifically, the damp, moldy environment of de Guia’s Baguio home, where his negatives are stored, took its course. The interactive pieces of Romina Diaz, Kawayan de Guia, Carlo Gabuco, and Lawrence Sumulong elevate audience participation beyond the invitation to visually engage with and interpret the images before them. The value of photography lies in its overarching capacity to democratize and validate one’s existence. Within the context of art, its shifting abilities to serve as multitudinous vehicles for critical inquiries are liberating.

The Not Visual Noise exhibition is a beginning as well as a continuation. The viewers’ ability to trust themselves as viewers is precarious due to an unconscious “fear” that they may not “understand” what they are seeing. These moments of being present and silent with a wall-bound artwork or photograph, collage of imagery, multimedia photographic and mixed media installation, or interactive piece can be jarring and uncomfortable. However, if such a place of experiencing is possible, then the photograph or artwork is no longer a part of the visual noise that can be readily seen in mainstream advertisements, social media, and entertainment industries but can be an experience of visual pleasure, provocation, and contemplation.

This text was initially published in 2019 as curatorial text for Not Visual Noise, curated by Angel Shaw, which run from 24 Nov 2019 to 28 Jun 2020 at the Ateneo Art Gallery. This article is republished with permission from the Author.

Comments